Los Angeles Times | MUSIC REVIEW : Cellist Geringas’ Talent Brings Shostakovich Piece to New Height

SAN DIEGO — The San Diego Symphony, after a flurry of media attention earlier this week over the appointment of Yoav Talmi as music director, returned to business as usual Thursday night at Symphony Hall. Guest conductor Klauspeter Seibel, who made his local debut, led the orchestra confidently through Mendelssohn’s “Ruy Blas” Overture and the Shostakovich First Cello Concerto. The veteran German conductor also did his best to hold the band together in Schubert’s sprawling “Great” C Major Symphony.

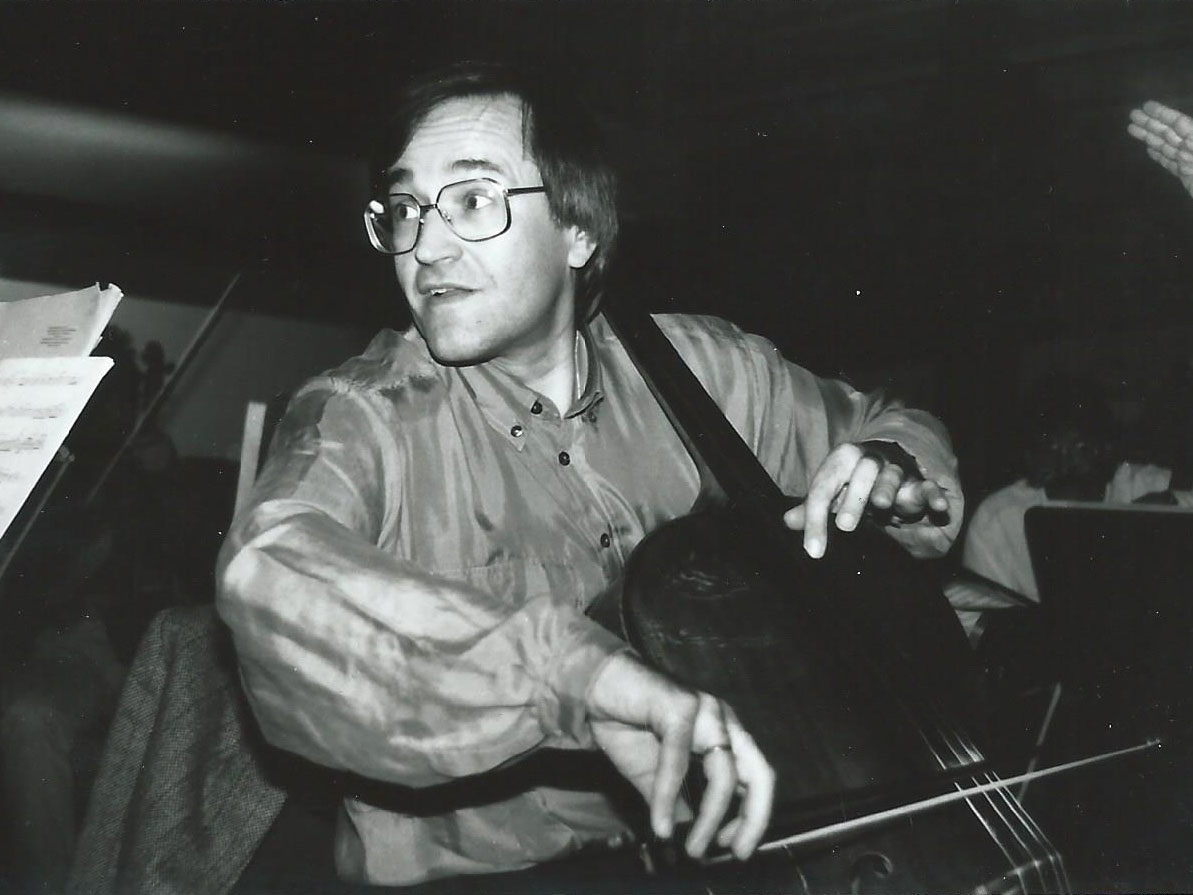

Nothing on the program could touch the brilliance of cellist David Geringas’ performance of the Shostakovich concerto, however. If he had merely met the work’s daunting technical demands, he would have rightfully claimed the audience’s admiration. The 43-year-old cellist, originally from Lithuania, not only transcended Shostakovich’s complex challenges, but he probed the composer’s overt and repressed passions with telling insight.

Geringas’ intense determination made the third movement, an extended solo that takes the place of a cadenza, a haunting traversal. Although this concerto was written in 1959 for Mstislav Rostropovich, Geringas’ mentor, the younger cellist clearly owns the work. While Geringas’ name is not a household name even among classical music enthusiasts, his is a major talent. His performance with the symphony made it clear that winning a gold medal in Moscow’s 1970 Tchaikovsky International Competition was no fluke.

Seibel proved a sympathetic and able collaborator in the Shostakovich, coaxing from the orchestra a supple, persuasive accompaniment. Especially in those sections where the forces are pared to chamber music scale, Seibel crafted clean, elegant balances. First horn player John Lorge carried out his extensive solo duties immaculately.

Although it was prudent programming to have scheduled the Schubert Ninth Symphony late in the symphony season, it would be inaccurate to claim that the orchestra was ready to take on this symphony of “heavenly length,” as Robert Schumann dubbed it. Schubert’s posthumous symphony calls not only for stamina, but for warmth of tone and unforced lyricism. In the opening movement, the orchestra came closer to precision than to grandeur, and in the lively scherzo, what should have been brilliant was closer to boisterous.

Seibel’s direction of the Schubert was full of conviction and painstaking detail, and he had the good sense to keep the tempos moving. He was more successful, however, in eliciting a polished and generously proportioned performance of Mendelssohn’s “Ruy Blas” Overture at the program’s opening. The brasses have seldom sounded more united in their throaty fanfares.